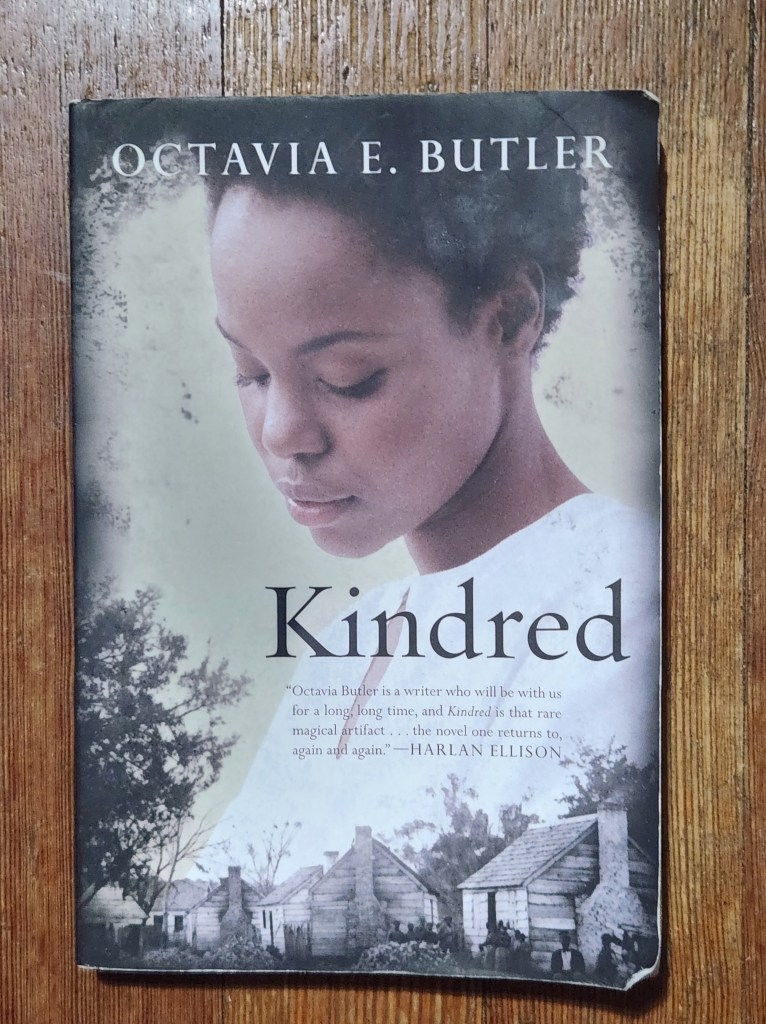

I’m excited to get the Deep Dark Night blog started again and will soon have an announcement of exciting events on the horizon. For now, I hope folks enjoy some thoughts on Octavia Butler’s classic Kindred.

I’ve reviewed Octavia Butler’s books before and always find her style to be close to my heart—like George R.R. Martin or Marc Behm, she has an edginess to her voice that defies attempts to make her safe. While her themes certainly thwart injustice with their critiques of present and historical power structures and cruel institutions, she also describes deeper existential issues with regard to family and the human capacity to reinvent morality moment by moment to suit not only survival, but to excuse greed and even evil, against one’s better judgment.

In the case of Kindred, I think it possible a reader might overlook title’s multifaceted nature, but in truth, the kin to whom it refers, the family which the young African American woman of the 1970’s travels time to the antebellum south to interact with, consists not only of the oppressed but the oppressors. This is not just a novel of the thirst for justice and a better world to come; it is a story of the intensity of emotions surrounding necessary parricide and the difficulty presented when a part of a person can’t help but feel a warped affection for their abuser. It handles not only the physical constraints the slaveholders impose, but the insidious kinds of brainwashing they gradually inflict on their victims.

Butler’s works are always courageously complex when it comes to relationships. The Xenogenesis series (possibly my favorite of her works) casts the mid-twentieth century American phobia of aliens invading our land for the purposes of breeding in a light that tints away from 1950’s “they want our women” into a twisting tale of forced evolution, of hallucination-laced sexual interaction with vaguely plant-like beings, and most importantly, the sentiment that when cultural change arrives, it affects every aspect of life and perception—physical, psychological, emotional, and even reproductive. Though generations seek to reproduce themselves, the opposite is always true—change is permanent, and never purely good or evil—only profoundly different.

In the case of Kindred, narrator Dana and her white husband Kevin, a pair of married twentieth century writers, find themselves dealing with the sudden necessity of living in the early nineteenth century under the yoke of the Weylin family, gun toting, disease-ridden plantation owners who handle their slaves like possessions not fully human. Souls and bodies are stretched like tormented victims bound to the rack. Dana allows her husband to present as if he owns her as a means of survival as she navigates a world in which the family’s slaves in the fields, cookhouse, and mansion live in oppression which they despise but to which they are also forcibly accustomed. Even free black woman Alice, whom Dana discovers is her direct ancestor, is sucked deeper into the maelstrom of oppression when she loses her freedom trying to help her husband flee to the north.

Dana discovers that surviving her time travel hinges on keeping the Weylin family’s heir Rufus Weylin alive long enough to have a child with captured Alice. Rufus purports to love the person he has imprisoned. The antonym of Stockholm syndrome, Alice can barely hold onto her sanity as she lives hating Rufus, and Dana comes to realize that this pair, her distant grandparents—her kindred—are the storm that brought about her existence. While she openly defies and criticizes the Weylin family for their cruelty and their embrace of the plantation’s violent practices, her heart and mind experience dizzying emotions surrounding her familial connection to them. There is a nauseating kind of rapport that develops between her and Rufus— she has a power over him that only a strange version of familial love can create.

Motifs involving parricide and family tragedy have always pervaded all forms of literature. From Oedipus to Tyrion Lannister, the nausea of loving and hating a family malefactor is the recipe for the desperate lessons our tales teach. The lesson in Kindred adds and underscores a more terrifying reality to this scheme—that the family violence can be institutional. Built into the very fabric of the American tapestry and the bones of our citizens is that slave and slaveholder are family—are kindred—and while Martin’s Tyrion Lannister may have shot his father in the privy with a crossbow, one or one thousand quarrels cannot shoot away the reality that we cannot murder our history and cannot remove, cancel, or delete the status of kinship. Bodies can be destroyed, but relationships remain and have to be dealt with. To feel the loves and hatreds that come with the storms of history is to feel them not about someone else or other, but about our ancestors and ourselves.

When Butler’s heroine Dana returns to the twentieth century, she passes through a wall that amputates her arm, ironically leaving a part of herself forever in the past. Thus, the novel ends by bestowing a reminder that, though injustices within institutions and families can come to reckonings, and though those who deserve it can be punished, such acts never come without sacrifice and, ultimately, the connection to kindred can never be fully severed.

Carl R. Moore is the author of Slash of Crimson and Other Tales, Mommy and the Satanists, and Chains in the Sky, published by Seventh Star Press. He has published numerous short stories in magazines and anthologies, most recently with Jumpmaster Press and Crystal Lake Entertainment. His new novel, Red December, will be released in July, 2024.