Passing through Portland Maine for the first time in two years got me thinking about my old novella Slash of Crimson and Other Tales which was published way back in 2017. 2017 isn’t all that long ago, but the story takes place in the Portland of the early 1990’s. I originally wrote it during a frustrating time in which a full-length novel manuscript had a near-miss being published by a mainstream publishing house. I had even travelled to Salt Lake City Utah for the World Horror Convention in 2008 to meet my agent and other authors he represented at a client dinner. The trip was educational and I met a lot of interesting folks. The agent’s efforts were appreciated, but didn’t yield results on this first round. So I ended up adrift in some doldrums about what kind of themes broader audiences wanted. I started writing Slash in a coffee shop in Albany New York in part as a satire of paranormal romances like the Twilight series. The idea was to write a story that started out as a romance then had everything crash and burn in the flames of hell.

So much for charming the romantics.

But this new novelette got published by a man named Armand Rosamilia, who at the time had an e-book company in the early days of e-books called Rymfire Books. He published a version of it with a demon-mermaid on the cover drawn by my wife Sarah and it was cool to have an indie-title out that people seemed to get a kick out of (the Splash meets The Exorcist with an unhappy ending—unless you’re the demon…).

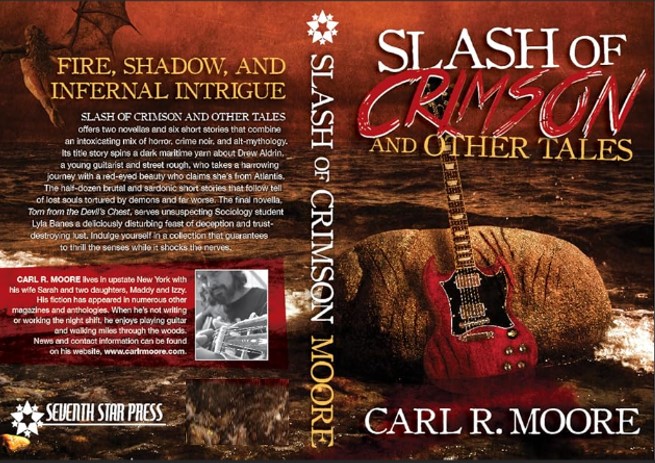

I went back to querying mainstream agents and submitting short stories to anthologies. After attending another World Horror Convention in Portland Oregon in 2014, I was again not able to sign a contract for a full-length novel, but did get a tip from Armand that a small press out of Missouri called Charon Coin Press wanted to re-publish Slash of Crimson along with a series of short stories in a collection which became Slash of Crimson and Other Tales. Jerry Benns, the owner of Charon Coin, had me expand the original novelette into a novella and had their amazing editor Margie Colton helped me turn it into a “director’s cut” of sorts. Unfortunately, Charon Coin ended up closing its doors before the publication date. Ever the fantastic folks that Jerry and Margie are, they put me in touch with Seventh Star Press and Stephen Zimmer who proceeded to publish the collection we had created and got the absolutely amazing Aaron Drown to make the cover image with the classic Gibson S.G. strutting its cherry and brimstone finish.

While Slash of Crimson and Other Tales didn’t exactly go viral, it reached a fairly high sales rank on Amazon and got some cool reviews. The story of a heavy metal guitar player in the 1990’s dating a girl he thinks is a mermaid but is far from it had enough humor amid the gore to gain some appeal with the aforementioned romantics.

Which leads us back to Portland—when I come through Portland now and think of the scenes in the novella, it is not the gore or violence that’s scary but how much Portland has changed since the time the story took place. It’s turned into a funny picture of what the only city in Maine was once like—I’ve even heard there is a copy that somehow ended up in the Augusta library (though I have never checked—the only time I stop in Augusta is when I’m being pulled over for doing a 91 in a 70).

So, in a Stranger Things-esque spirit of nostalgia, here are some examples of the state of affairs in the old-school Portland from Slash:

- Munjoy Hill is a slum

- Rock bands have a dozen or so venues to play at

- The basement bar is based on a place called Leo’s

- People can smoke all over the place

- Drummers drink 40’s

- The Porthole is a dive

- Run down buildings on the waterfront are rehearsal studios, not condos

- Feral cats run rampant on the docks (this may still be true, but I didn’t see any while drinking craft beer at the new Porthole)

- When playing at the old Porthole, bands got paid $10 per member and all the fish you could eat

- Proselytizers for standard Christian churches as well as fringe cults (including Heavens Gate) regularly and openly preyed on students on the USM campus

So if you’re thinking about what to choose for beach reading (and maybe even heard my pitch for Red December’s winter terror-fest) and are looking for something with a maritime aesthetic, a touch of the erotic, and some spooky action, maybe give Slash of Crimson a shot. There were once plans pre-pandemic for an audiobook format, which I hope may be revisited, but for now, it is available in e-book and print formats.

Carl R. Moore is the author of Slash of Crimson and Other Tales, Mommy and the Satanists, Chains in the Sky, and Red December, published by Seventh Star Press. He has published numerous short stories in magazines and anthologies, most recently with Jumpmaster Press and Crystal Lake Entertainment.