The fact this is the second obituary-style blog entry in a row reveals how intense of a transition I have been going through the past few years. We assign our years numbers but really the rapid changes have occurred from about December, 2024 to today, March of 2026. It began with a few of my own health problems then continued with some surgeries for my wife Sarah. These events combined with managing our kids’ transitions from high school to college, our house’s incremental evolution from a family home to a proverbial “empty nest,” and another major event, namely my father’s end of life arc as exacerbated by dementia and cancer presented challenges to the whole family.

This is the reason that my blog, once updated regularly and called Is that an Old Book? and later Deep Dark Night, and which normally focuses on reviews of horror and fantasy fiction, has mostly been on hold and when updated, only for the purposes of a memorial and biographical content. Yet I feel that there are times when one must recognize that following rather than fighting a detour is the quickest way forward.

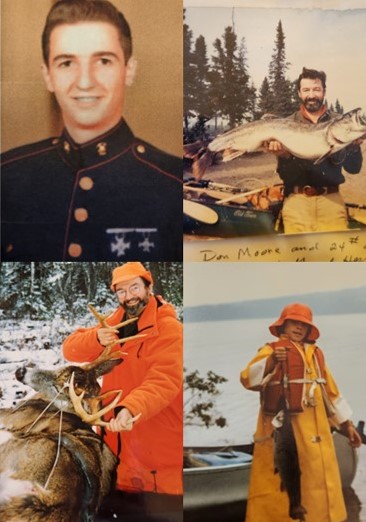

What follows is what I will call the completion of a cycle, a memorial for my father, business teacher and United States Marine, Donald E. Moore.

My father was born in Ellsworth, Maine, the son of Carl R. Moore Senior, local business owner and his wife Harriet Moore (who, as my dad often pointed out, had the same maiden name, Moore, as her married name). He usually said it with a wink like it was a tolerated joke about country folks and cousins, but while they were not of course cousins, the awareness of rural roots pervading all things was a theme worth noting. I will not spend more time here talking about the typical obituary content that can be found in his official obituary in the Bangor Daily News, but suffice it to say the identity of his formative years were forged by the beauties and struggles common to many rural Americans in the 1950’s. His father sold and repaired cash registers and typewriters and was a sometimes lobsterman. His mother raised the four kids. Without going into too much depth about them, I’ll add that old Carl struggled with a clichéd fondness for the bottle which is likely one of the main reasons for his parents’ divorce.

For young Donny, the biggest tragedy of his parents’ separation was that his mother extracted him from Maine and brought him to Milwaukee, Wisconsin. This is tragic because during his earlier boyhood years and in spite of their economic challenges, he developed an intense passion for being outdoors. He loved going fishing with his father and talked about how exciting it was, even when the old man wasn’t around much, to be picked up and driven to a faraway stream in an anonymous patch of woods where Old Carl would teach him how to catch tiny brook trout whose tails, when fried and salted, were crunchy like a potato chip.

Don would tell me these stories when he took me fishing at “Secreta Stream” when I was a kid. “Secreta Stream” was any stream in Maine where you were the only people there so no one in the entire world knew you or the stream existed, and if you were playing hooky from something lame you were supposed to be doing, that was even better, though only if you had earned this furlough, but more about that later. The way he usually told it, Old Carl would tell young Donny, “Now you go east and I’ll go west and we’ll see what we can get.”

“And one day I caught this big fat fish all by myself and I was so excited and I couldn’t wait to tell my dad!”

“Was he impressed?” I asked.

“No,” Don said. “I brought him the fish and said, Dad, Dad, I got one! And Old Carl said you did? Let me see. And I showed him and he grabbed it and said that’s a chub, and threw it up into the woods.”

“That sounds awful,” I said.

“It was so fun,” Don said. “I loved fishing with Dad. I loved being outdoors in Maine.”

Don described his later move to Milwaukee as a boy sinking into what sounded like a depression. He was placed in parochial school, which he despised. He spoke of filthy canals, arduous paper routes, fights with other boys, broken bikes, futile crushes on girls and an utter yearning to get back to beautiful Maine. In deference to the greater Moore family, I will not go into too much detail about his dark time in Wisconsin as it relates to Maine roots. The elders who were there may have a different take on this time, but please keep in mind I am only giving the angle I had as his life was described to me by the man himself. I, too, am a Moore, and Don’s tales of his extraction from the country and how it affected family strengths and weaknesses and all that followed had a profound impact on my own development and my own closenesses and distances among the wider kin.

I’ll put it like this—I called Old Carl’s issues a “clichéd fondness for the bottle.” I will couple this with the reality that there is a brutal nature underlying Appalachian American culture (and I consider Maine to be Appalachian; many would disagree but that is a debate for another time). This culture possesses a certain unpredictability which along with fried fish, swimming holes and jamborees always promises that the good times can quickly change. The “I-love-yous” of a hangout among kin (and I’ll try to keep this a little Norman Rockwell for the sake of civility) can turn into trading harsh words with a side of knuckle sandwiches, extra pickles, on the flip of a rusty dime. For more on this theme anyone can easily look up pop culture hits like Deliverance, House of a Thousand Corpses, or our illustrious vice president’s opus Hillbilly Elegy. I think that last one is the scariest by far.

So young Donny was living in Milwaukee unhappily and getting in some teenage trouble brought about by family challenges and cultural forces. He had a good heart and even some ambitions. He used to mention how he had an awareness that folks with careers could get out of bad situations and build good lives. He showed me an article written in the 1950’s in a local paper where a journalist was interviewing students and he was quoted as saying he wanted to be a doctor. Instead, at some point, he ended up in some form of juvenile detention. Luckily, his mistakes weren’t too terribly awful—hot wiring cars, something like that. I mention this because, as he told it to me, it was during this detention that he spoke with someone who changed everything—a Marine Corps recruiter.

In another essay I wrote about one of Don’s colleagues passing last fall, I quoted Don as saying, “the Marine Corps was my mother and my father.” He said it more than once and meant it. He joined at age 17 and suddenly the world made sense. There were orders to follow but there was also respect and independence and a sense of accomplishment. Most of all, there was a plan and a way forward, and, eventually, a way back to Maine. The military made him physically fit and honed skills that would be useful for an outdoorsman. It dropped a little money in his pocket and put an education within reach. I will not go into great detail about his time in the military and only say that he spent most of his time in the Pacific and was out before Vietnam had fully escalated.

True to his passions, after he was honorably discharged, he returned to New England and lived with his brother Buddy in Connecticut while the two saved some money and went to school. Don was a serious student, got a business degree and teaching certificate. I mentioned earlier that we had once played hooky and gone fishing. This was the statistical outlier to his profound sense of duty in all things and his conviction that what good you enjoyed absolutely must be earned. He continued his ‘military’ lifestyle during his college years—short hair, pressed shirt and collar. He also bartended on the side and met my mother in New Haven. A teaching job followed and soon she was pregnant with me and he brought his family back to Maine to live his dream.

Unfortunately, it wasn’t long before he and his urban wife parted ways. He tried very hard for it not to be as rugged as his own parents’ breakup, and in many ways succeeded, though for me it was rough enough.

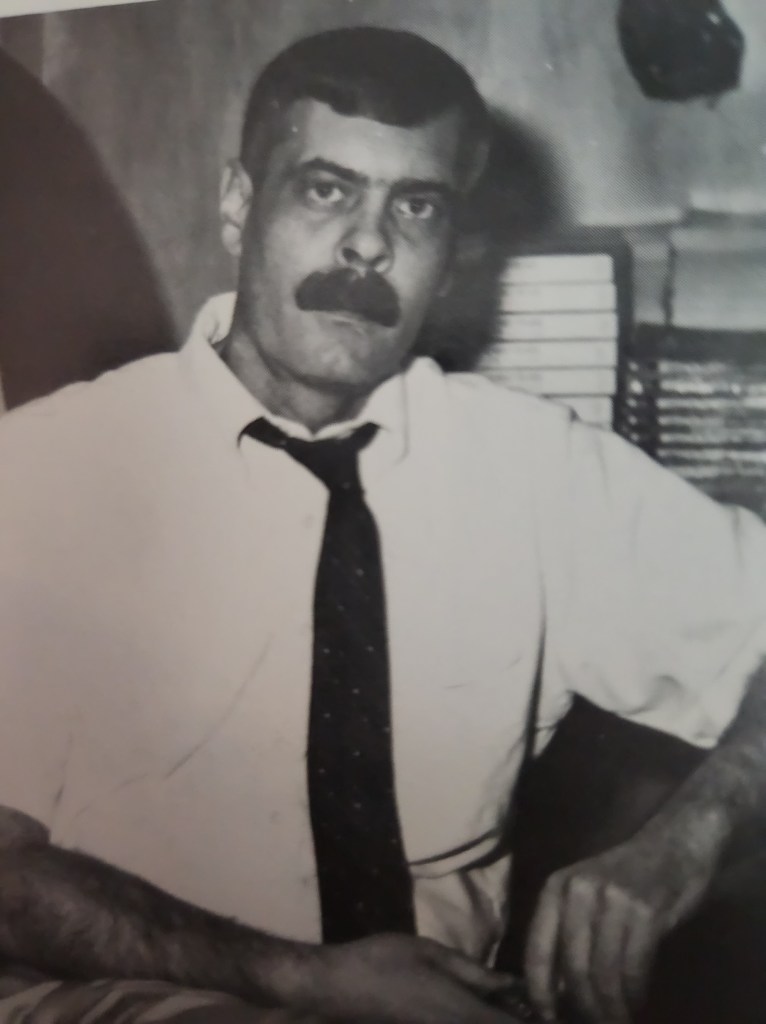

Still, Don had achieved some successes that would prove to be extremely rewarding. Though he had not become a doctor, he had found a niche in Orono High School as a business/vocational education teacher working with kids who he considered to be ‘like him.’ He was a natural carpenter and had a reverence for working with his hands which earned the respect of these voc students. Orono High School was a bit of a “yuppie” school in what in Maine might be called an ‘upscale’ town, and so the vibe had what I would call a “town gown” relationship with itself. I mean that there was a kind of separation between the Ivy-bound students and the kids who were entering the trades. This was a perfect niche for my father. He loved the Maine landscape, loved hunting and fishing, but he also worked around his disdain for the murkier side of Appalachia by embracing an almost “Beatnik” relationship with woodworking and deer-skinning. Though he might not describe it this way, he saw the “poetry” in the outdoors and the trades. He was less Hillbilly Elegy and more A River Runs Through It.

Which leads us to the jewel of his successes—a log cabin he built on Junior Lake. Sometime in the 1970’s, while on a fishing excursion, he found a cheap ramshackle cabin for sale in Washington County, not far from the border of New Brunswick. He was still married to my mother then but managed to purchase it in a time when such things did not require wealth, particularly if you were going to supply the sweat equity. I remember the old cabin before he tore it down—it was M-shaped and infested with spiders and mice. My mother liked the lake but the fact you had to drive to one lake, unpack the truck, load the boat, fire up your five-horse-power Evinrude motor, chug up a swampy stream for 45 minutes, cross another lake, unpack the boat, carry the heavy cooler up to the porch and then make dinner without running water to clean the plates was more than she signed up for.

Also, without going too deep into this subject, I was a sickly kid, so the trips to the camp were a bit of a challenge for me as well. I had weak lungs, a torment, and the moldy cabin didn’t help

But I still loved it.

The chain of lakes had an ancient quality. The stars sparkled, but the darkness between was impenetrable. In the winter, the ice sang and moaned as it cracked, in the spring, the wind whipped up massive waves, and in the summer choruses of frogs, owls, and splashing fish filled the moth-ridden night.

One of the first stories Don told about the camp after buying it (and one of my favorites when I was an eight-year-old-boy because it nearly involved a cowboy-style shootout), was a confrontation he had with the former owner. Don went up to the lake after the closing only to find the former owner loading up his boat with the camp’s furnishings and contents.

“I told him that’s not what we agreed.” Don said. “I was getting the camp ‘as-is,’ furnished and all. But this guy wasn’t having it. He confronted me on the shore, showed me he was wearing a pistol on his belt and said, ‘You think you can take me?’ to which I replied, ‘Oh, no sir, so sorry. Here, let me help you load.’ So I helped him carry stuff out of the camp and when I found something I liked, I waited ’til he turned and bent over the boat then threw it up into the woods.”

Chattel secured, Don tore down the old camp and built a new one, a masterpiece of DIY woodworking. He remarried his second wife, Paula, the love of his life and a companion in her passion for the outdoors. Don generously allowed me to bring my school friends to the cabin and took us all fishing on the reg. We went “perching” in the evenings when there was a bag limit of 25 perch and often caught close to that limit, which we could take home and fry. Your belly was already full of snacks from the good times on the boat but you’d been outdoors all day, so you could eat it all.

I absorbed Dad’s joy on these days. The happiness on the lake was genuine and profound, but I also understood there was a darker current underneath. What he had gone through to get these glimpses of paradise was no small feat. Career, family, military, divorce—the feeling you got when it was time to go home after a fun weekend and you hoped you stopped for ice cream but either way, duty called and you’d be up at 6:00 a.m. for work and school.

Though Don had a disdain for Appalachia’s brutal side, he was also suspicious of another type of outdoor culture. As much as he had reconciled the town-gown part of our school, he was wary of any who thought they could “buy” their way into the experience. Though he had friends who were Maine guides and who encouraged him to become a guide himself, he had no interest. I, in turn, witnessed and understood that the outdoor life was about more than just taking little kids perching. There were antlers all over our house and the camp. Antlers were door handles and cupboard latches and coat hangers. These came from the deer that hung in the garage in November. A close family friend named Jim who owned a sporting goods store recently remarked to me on how they all admired how early Don would wake, in the range of 3:00 a.m., to drive to a stand built deep in the woods. He also possessed evidence of more ambitious types of fishing—long, broad Atlantic Salmon mounted on the wall.

I knew that this was another level to the outdoor life. I knew that the venison that supplemented our diet and the salmon filets on our plate came from the development of skills that took hours of constant attention and practice.

I remember one fishing trip when I was around ten which was not basic spin-casting. We were trolling in deep water with longer lines and spoons. He was making me choose the bait and becoming more earnest in his instructions about knots and setting the hook. I wasn’t having much success, choosing lures that were bright orange and green and kinda looked like Star Wars figures. Don said, “Some lures are for catching the fisherman, but I want you to catch a fish. You gotta fool the fish.”

After more hours without success, I found a slightly curved gold spoon. I thought it looked simple and funny. I asked Dad why it was curved and he said so it moves like it’s alive, it flashes and turns like it’s real.

The flash worked and I hauled in a five-pound smallmouth bass that afternoon. It wasn’t typical bass fishing. It was midsummer, and deep water, and truth be told, I wanted a lake trout or a salmon, because those were somehow “game fish” in a way that bass weren’t. And yet, it was a real fish, and we celebrated. And the fact that he talked about it so much to his friends filled me with a sense of accomplishment.

In the years that followed, fishing was what Dad and I had in common even as the rocky teen years approached. He threw fantastic birthday parties for me and my buddies when I was a tween. He’d fry us up some dinner and give us a cake then sneak outside, put on a gorilla mask and chase us around, doing battle like he was Grendel and we were a band of Shield-Danes. Even our house in the town of Orono was surrounded by woods and fields, so the night games were thrilling and held a sense of danger. We tried to outsmart the monster but he easily slipped behind wood piles, climbed a tree, hid in the high grass, then ambushed us and sent us scattering. He hide behind a tree, then throw a lit match in the driveway and we’d all run after it, then he’d dash in the other direction and ambush us after.

“Easily fooled,” he said to me after one of those nights.

The last birthday party occurred up at the camp when I was thirteen.

“You’re going to have a Bar-Mitzvah,” he said.

We are not Jewish, but he deemed it a good idea to consider me a man by that ripe old age. In general, he considered kids to be coddled in our society. Of course, he didn’t mean it was time for a thirteen-year-old to move out, but self-reliance better damn get started. By that time, things were getting confusing. On the one hand, he had a great respect for the high professions, doctors, lawyers, what have you. But as my own adulthood loomed, I sensed a disconnect. Something wasn’t right about the concept of seven years of school after graduation, and who was going to pay for it? My health problems had only gotten worse and the military wasn’t going to be an option for me. A great deal of bitterness remained between him and my mother. In contrast to his vision of the American program, a simple, emancipating gesture like running off to join the service was not going to untie these tangled knots for me.

If I was going to learn to be an outdoorsman, it was time to pick up a gun and go hunting. It was time to figure out how to get a driver’s license, an obvious necessity for fishing and hunting. It was also time to cut my damn hair and get serious about something, about anything, lest I end up adrift without a paddle. Things were getting edgy. Some of my close friends witnessed it. Many of the boys who had come to the camp with me, one Fran Cathcart among them, remarked on Don’s temper. We all worshipped him and his outdoorsmen buddies, but his patience was particularly short with me. He could filet a fish like an artist and he would lay the fish on the cutting board and show us how to carve around the bones and I tried but it wasn’t long before I wanted to go play Dungeons & Dragons or go play guitar.

Still, when we hungout, we had fishing. On the good days, we’d go out in his boat and use his tackle (at fifteen, though I had been Bar-Mitzvahed, I still couldn’t afford lures). He had this routine where we’d start trolling, and he’d wait until you cracked a soda and looked away daydreaming. He’d then reach out and yank your line so your reel spun.

“I got one! I got one!” I’d shout.

I’d then turn to see my fishing line in his hand and a shit-eating grin on his face.

One time, in the waning days of the fishing years, I brought a friend named Nick with me up to the cabin. Nick was a tall, smart teenage kid with an academic bent. He admired Don like most of the young guys did and that was cool but that particular weekend Don had brought a friend named Steve with him. Steve co-owned the aforementioned sporting goods store with Jim. Usually, the two of them came together, Jim being good-natured but slightly more earnest in his sportsmanship and business sense and Steve being a bit of a mischievous type (on the mischief spectrum, I don’t think any of these guys lacked, Don included, though we might respectfully say Steve was a tad extra). In 1980’s parlance, I saw Steve as kind of Chevy Chase meets David Hasslehoff decked out in Gore-Tex, and our little Beavis-and-Butthead asses thought he was the coolest.

Don and Steve decided that on the trip’s middle day, the men were going to have a fishing contest. Many prizes were proposed among the parents and wives—soda, respite from chores, a stop at the Snack Shack on the way home.

But Steve said, “No. Listen. Whoever catches the biggest fish… wins.”

“Whattaya mean?” the boys asked.

But Don put a pause to it. He looked thoughtful for a moment then said, “He’s right. Whoever catches the biggest fish, wins.” The way he emphasized the word wins, all instantly understood.

We rose the next morning early and hopeful. Don and Steve took my dad’s newer boat with the steering wheel and 25-horse power motor. They had all of his gear including an electronic fish finder, innumerable lures, knives, gaffs, and nets.

Nick and I had the canoe, our rods, a tiny tackle box, and net.

The teams set out onto the lake, Steve calling back, “You guys have the advantage, really, you know, quiet.” Then they zipped off and began casting, cove by cove. Then they trolled, then headed down the stream. We began an arduous paddle to a small pond rumored to have big bass. We exhausted ourselves just getting there then caught nothing once we did. We came all the way back to the big lake where Don and Steve zipped over to check in.

“Get anything?”

“Nah.”

“We did,” Steve said.

Don held up a stringer with a few small pickerel. “Pickerel-trout,” he said. He called them that because the alligator-like fish were normally much bigger and these were so scrawny. He wasn’t impressed with them and neither were we and yet they had fish and we didn’t and if we didn’t do something about it, they were going to “win” and we were never going to hear the end of it, likely for the rest of our lives and beyond.

Their boat zipped away with its gear and fish finder and we kept paddling, knowing there were only a few hours left. The waves were kicking up on the lake and we formulated a plan that we would try to go back past the camp into the swampy cove and see if we couldn’t get a larger pickerel ourselves. It seemed like a better bet and in the meantime, as we crossed the middle of the lake, I thought a flashy spoon might hook a salmon if we trolled it. Worth a try.

We got almost all the way to the camp and had almost all of our line out. I was paddling, Nick was holding the rod. The reel spun, Nick pulled, and a huge fish jumped out of the water. It was a bass that had gone deep in midsummer like I’d hooked once when I was a kid. Nick reeled furiously, but not only did we have a lot of line out, we were fighting two-foot waves in a small canoe in the open water and tipping left and right. I was having a hard time paddling against the wind though every foot counted as we approached the camp. Nick got the fish close to the boat. I lifted the net, but in its tangled state it was flat like a tennis racket. Even worse, we were about to knock sideways against the rocks, and if we dumped, all was lost.

I was a complicated little hippy back then and still basically am. I had no finesse and though these outdoor adventures were fun, in that moment, I lamented my lack of skill when it came to solving the problem the way a more experienced angler would. My buddy was still having a good time (I think), but I dreaded what would happen if we didn’t land that fish and its implications for the way things were going between me and Don.

So I jumped out of the boat.

This wasn’t the right way to do it and it was far from photogenic and even further from being a believable story.

But I jumped out of the boat in whatever I was wearing. I kept hold of the net with one hand and put the other on the canoe. I kicked off the rocky shoreline which pushed the boat back out into the deeper water long enough to swing the gnarled net like the tennis racket it resembled. Nick had the bass in close to the canoe by that point and though I could easily have gotten stabbed by the barbed hook, instead I managed knock the fish up out of the water and into the boat. There were some nervous seconds when the bass shook off the hook, but Nick was able to subdue it while I swam the canoe in to shore.

It was a victory. We “won.” Don and Steve came back without anything more than their pickerel trout. We milked it, saying “Get anything? Huh? Get anything?”

Steve shook his head. “Uh oh, um Don, um uh oh…”

Don was great about it. He took the bass and traced it on a brown paper bag, something we did when someone had a remarkable catch. We went through another fileting lesson. He was nice about it—I don’t remember any “Goddamnit, Carls” that day, only joy and jokes as the spouses emerged from the cabin to witness the After-School-Special of a contest conclusion.

And yet it was bittersweet. In those days, things had changed. I could handle a canoe on a windy lake. I was a half-decent fisherman as long as it was a spin-casting reel and we weren’t fly fishing. I was even a strong swimmer for a guy whose lung disease had limited his life options.

And yet I felt a space between developing between me and Don that I knew wasn’t going to get better anytime soon. It wasn’t that he didn’t accept his hippy son so much as knowing that there was something we wanted to share but hadn’t quite been able to pass between us.

Years passed. I grew up. I liked playing in bands and spent a lot of hours playing and writing songs and stories, but I also spent a lot of time partying and watching movies and reading books and at times just being lazy. Now, this is Don’s memorial, it is his story, not mine, and yet the way he raised me is a part of him, though it sent me on a certain trajectory. My winding path took me out of Maine in a way that didn’t share the sense of purpose he had when he left with a vow to return. My path took me far from family. There was distance of all kinds in those years. We crossed out of teenage-type troubles and yet there was a deeper emptiness. I recognized what Don had accomplished by pulling himself out of the troubles of his childhood, and while I had my own troubles and goals, my father’s role in my life wasn’t clear and there were little funny-bone-lightning-strikes of estrangement as I wandered to Southern Maine, Asia, Europe, and New York City figuring which road was right.

Years later, I achieved a modicum of stability. I married an amazing artist in New York City. If you hustle and work hard in New York, opportunities exist. You can live in that city and the higher income can offset the higher expenses. It occurred to Sarah and I that if I kept my gig in the city (which here I’ll just call “niche corporate” and leave it at that) and we moved to upstate New York, we could afford some property and raise our kids with some space. I became a long-distance commuter, taking trains and busses to New York City twice a week for my night shift. The position itself was challenging, but the commute added to the challenge. There were times when I’d travel in poor weather and end up soaked and needing to change into corporate attire and then return home and get soaked again and sleep that way. Nowadays, I can work remotely more often and that’s a huge benefit. I have grown into the company in a way that is satisfying and, with our daughters nearly grown up, am buying some acreage in the western Catskills where one can hunt and fish and camp and pick guitar under the stars.

Yet in the earlier days, when our kids were young, I had the needling feeling that I had to make sure things were right with Don. I wanted Maddy and Izzy to know their grandfather and his unique relationship with the outdoors.

I became a father young enough that Don and Paula still had the camp on Junior, and we went there in the summers with the girls. They loved it all and went “perching” and swimming and ate smoked trout on a fire while the owls hooted. Don’s spirit and generosity were still strong and I was thankful.

One time he took us out in a beautifully wrought, all wood, flat-backed Grand Laker canoe that he had made in his woodworking shop. He’d given up the boat with the steering wheel and gone back to the outboard motor controlled at the stern. He’d also gotten this giant, colorful Chinese dragon kite for the grandkids. The idea was get the boat going fast then unfurl the kite and send it aloft, the wind generated by the boat’s speed. Maddy and Izzy were so excited and couldn’t wait to see it fly.

“All right, Carl,” he said. “Take a hold of this spool and let out some line, then I’ll start the motor and up she goes!”

I nodded and did as he said and the kite took off, flying high.

So did the hippy. Hands still on the spool, I was tugged from the boat and landed with a dramatic splash in its wake.

Don came around and picked me up.

“Oh no, Carl, are you okay?”

“Yeah, Dad, I’m good.”

“Great, sorry, let’s try it again, we’ll be more careful. Let me know when you’re ready this time.”

“Okay,” I said, standing with the spool, positioning the kite.

I was winding the string when Don guns motor, kite flies high, hippy goes splash, and granddaughters explode again with laughter.

Don brought the boat around, shit eating grin on his face. “Gee, Carl, are you okay?”

“Yeah, but I think I’m done swimming for today.”

I thought, okay so it’s hard enough cleaning a fish and skinning a deer, but do you have to rub it in? I was also laughing of course. But I wondered. And I thought about it.

More years passed. Don enjoyed a long retirement. He had been a successful teacher and by the end, a director of a vocational school in Ellsworth. He was a Maine boy come full circle. Perhaps he didn’t become the doctor he had mused about when he was a kid, but then again, would it have been better to have the money to hire a guide, or simply eat the trophy buck you shot yourself?

In his older age, before the dementia set in, I was able to visit Don at the camp a couple of times on my own. He was over it with the fishing by then. He hunted for as long as he could, but getting the boat out on the lake for a few slimy perch just didn’t do it for him anymore. Although I hadn’t been fishing as much either, when I came back on these last trips, I still liked to paddle the canoe out and catch perch and bass, the simple kind of fishing that still got you something to eat.

On one of these trips, I came back with a fairly full stringer. I put it on the rock by the shore and began rinsing the fish off one by one. Don came down from the porch and said, “Damnit, Carl, what are you gonna do with those? The ravens are gonna steal ’em. You shoulda let ’em go.”

“I’m gonna eat em,” I said.

“Oh yeah?” he said. “And whose gonna clean em?”

“I am,” I said. “I know the technique now. You taught me well.”

“Oh yeah? Show me!”

“Okay, watch this.”

I picked up the fileting knife with a firm but careful grip. I started cutting on top, behind the gill, and along the spine. I pushed the knife through and began to lift the filet, but instead of a neat flap, I didn’t go deep enough and left too much meat along the bone before pulling away from the tail.

“Goddamnit, Carl!” he said. “That’s not what I taught you! Gimme that damn knife!”

So I handed him the fileting knife and he started in, “Now I told you, you gotta feel along the bone, let the knife do the work…”

He went on with the instructions, working quickly through one filet after the other with the virtuosic touch of a master outdoorsman. I made my way back up to the porch unnoticed until I sat down in the chair and cracked a cold one.

“Damnit, Carl, aren’t you ever gonna learn? Now come down and clean these fish!”

“Nah,” I said. “You’re doin’ a real fine job. And they’re almost done.” I gave him a shit-eating grin.

He gave me an odd look back. Was it pride?

Don passed away peacefully in the memory care unit of the veterans’ home in Bangor, Maine, on the morning of March 1, 2026. The family kept vigil for several days and anyone who has gone through this experience knows it’s a swirl of reflection, frustration, patience, sorrow, and love. For me, my father’s love of the outdoors made it harder to handle the traditional religious notions our culture affords us in these situations. The general Christian ideas usually put forth in our neck of the woods, with all due respect to folks’ personal beliefs, offered little solace. When I think of Christianity, I often think of a verse in the Gospel of Matthew where a woman who is a widow of seven brothers asks Jesus which one will be her husband in heaven. Jesus answers, “in the resurrection they neither marry, nor are given in marriage, but are as the angels of God in heaven.”

Now I’m sure there are many interpretations for this parable, some scholarly, others more intuitive, all heartfelt. And to be fair to Jesus, he may have just been trying to help a gal out—it is hard enough to be married to one husband for life, let alone seven for eternity. But for me, this parable only underscores a cosmic view that the details of your life are not very important after death. And while there are notions of salvation and judgment in the Bible, ultimately, the message that comes through to me is that the world and all that is in it is secondary to what comes next. And so as I thought of Don and spoke to him in our vigil, this did not bring me comfort. If the end of all identity is the result of all identity, then what’s the point?

To me what works better for goodbye is the tangible truths passed on. The taste of a fish, the sound of a song. The flash of a lure, the feel of a guitar. To die well is to exist in the memories of your kin, your actions, and your possessions. These memories then live among all of us, themselves tangible actions that can continue without limit. As put in the Norse poem The Havamal, “Cattle die, and kinsmen die, / And so one dies one’s self; / But a noble name will never die, / belonging to one who has earned it.”

The Bible quote comes from the King James Bible. The Havamal quote comes from Bellows’ translation, slightly revised for context.

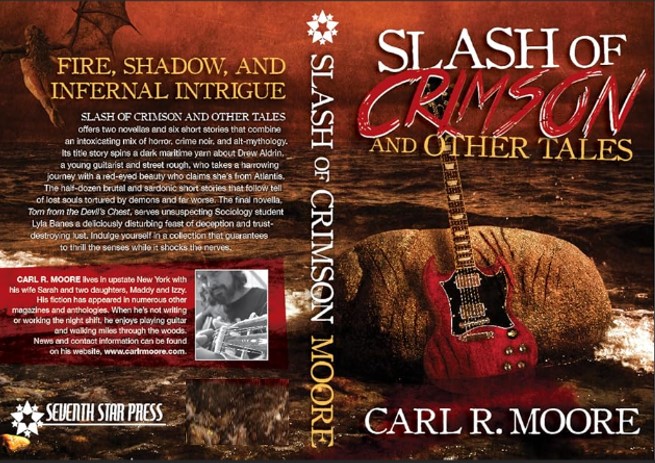

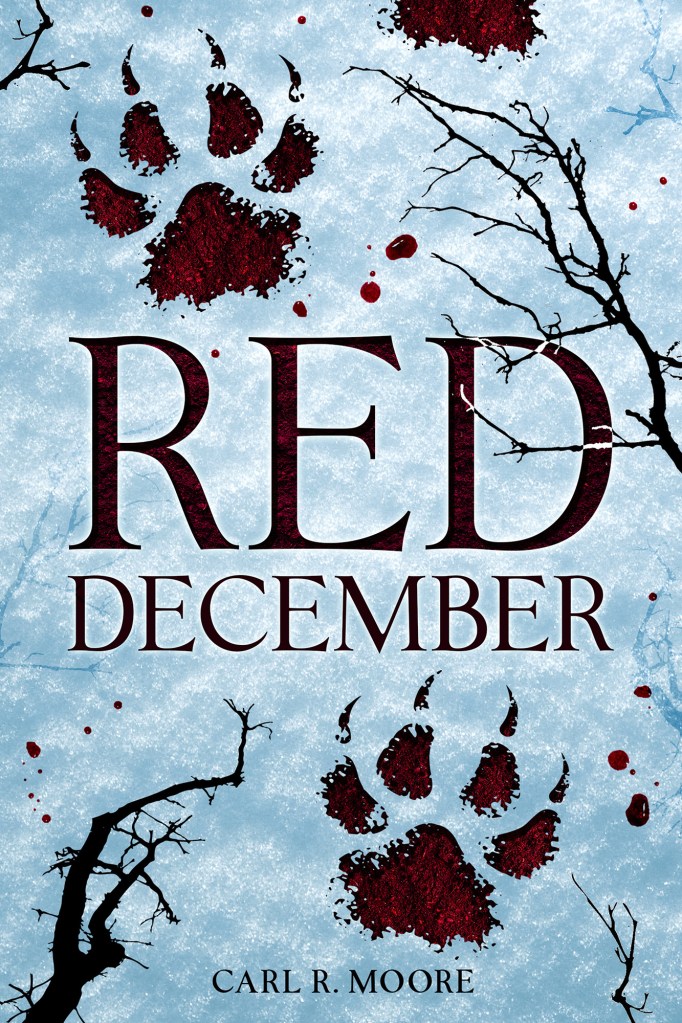

Carl R. Moore is the author of Slash of Crimson and Other Tales, Mommy and the Satanists, Chains in the Sky, and Red December, published by Seventh Star Press. He has published numerous short stories in magazines and anthologies, most recently with Jumpmaster Press and Crystal Lake Entertainment.