My once thriving blog has fallen into some neglect this year. This was not for lack of reading, writing, and thinking about posting. I was going to return to it with a new set of reviews for the Is that an Old Book? series, however, in light of a friend’s recent passing, the blog will be renewed with a different kind of essay.

I was on the fence about whether I would write something to mark the passing of Alexander McLean, an exceptional high school English teacher from my home town of Orono, Maine. I share with him a disdain for the sweet and sentimental. F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novels warned us against the maudlin, something I first learned in Al’s classes. I decided to go ahead in spite of this. The result follows below. I will add here that while some of the quotes are verbatim, others are close paraphrases, as best as I can remember them.

There is such a thing in American culture as what I’d call “the myth of the hero English teacher.” Nowadays it would be called a “meme” or just a “thing.” Is that a thing? Yeah, it’s a thing. Late Twentieth Century cinema brought us Dead Poets Society and Dangerous Minds, movies that glorified teachers who went above and beyond to inspire students to be passionate about good books. These stories gave us characters who were selfless and altruistic and kept private school kids from growing up to be shallow plutocrats and helped impoverished urban youth “get out of the ’hood.” But I am not aiming to emulate these themes. The influence Al had was too subtle and potent to be lumped in with these overwrought bon-bons of pop culture.

I thought instead to write an “anti-obituary” in the vein of Chilean poet Nicanor Parra’s coinage of the term “anti-poetry”—meaning that which defies convention. But, as Al would put it, there is a concern that in our internet culture’s anti-intellectual fury, the meaning would be misconstrued as being simplistically negative. So I’m going with “Un-Obituary” in hopes a more useful message comes across.

I’ll start with this quote: when asked what he loved most about teaching, Al answered “Reading by a lake in the middle of July.” I thought it funny and apt. You wouldn’t see this rawness in some masturbatory movie about altruism. But that didn’t mean he was any less committed to quality teaching. Instead, it meant he knew that honesty carries more weight.

My father, Don Moore, was also a teacher at Orono High School. He taught business and other classes that amounted to “Voc Ed.” He grew up a working-class country kid who used (needed) the United States Marine Corps to obtain an education. I think it ended up being more than that—he often referred to the Marines as his mother and father. It led him to a teaching career helping kids who he saw as “being like him.”

Al McLean, from what I gather about his early life, had a somewhat similar trajectory. He was a Maine boy who entered the military during the Vietnam War, served overseas, and returned to become a teacher. And while he and my father were colleagues, Al took a somewhat different direction in that he had discovered a love for literature and books and what we might colloquially call “the intellectual life.”

Al mostly taught American Literature. He was especially passionate about Hemingway, Faulkner, Fitzgerald, and Melville. When I was a freshman at Orono High and sat down for the first day of one of his courses, he had us write a paragraph describing in what ways we were “poetic.” My paragraph stated that I was not poetic. I stated that I had no interest in poems and novels (aside from maybe Conan comics and a few H.P. Lovecraft stories).

At that time, Al had a look that included a “Nietzsche” mustache and a collar and tie. He came across as stern. I was a little metal-head punk whose hippy side hadn’t come out yet. I wore ripped jeans and bandannas and a jean jacket with a Motley Crue patch on the back. I made my obligatory effort to get through the first novel he gave us, John Updike’s Rabbit Run, but it was a poor effort. I barely passed the class.

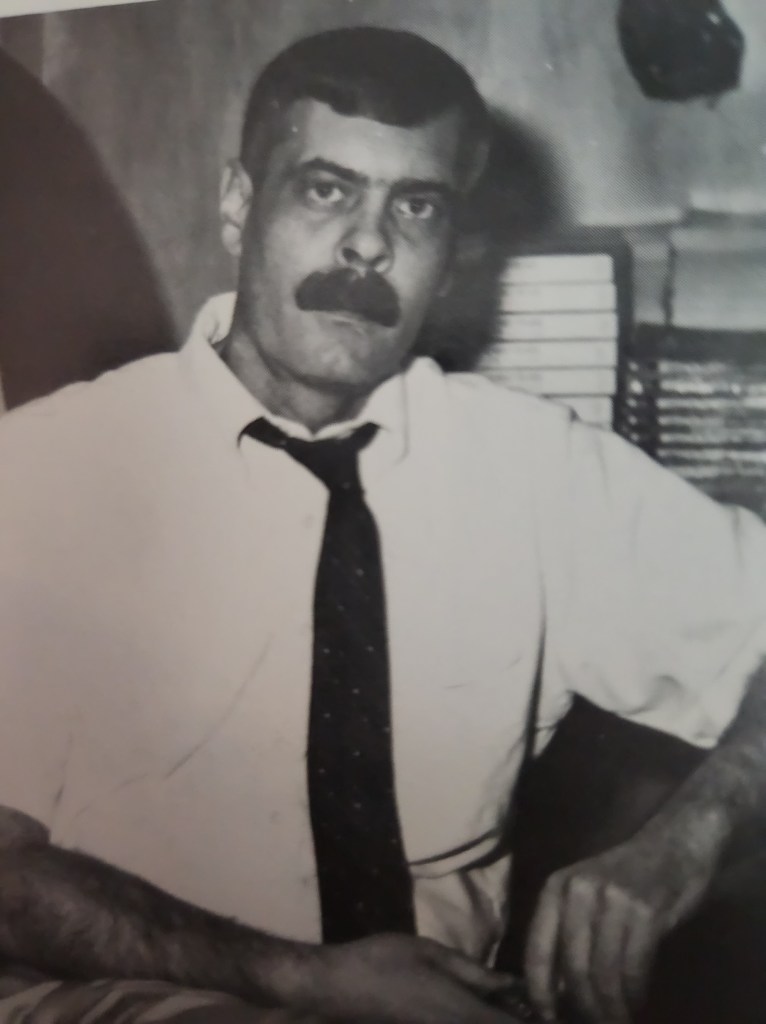

Photo A. McLean from OHS Yearbook, 1989

Our school had this system for freshmen and sophomores where we rotated among three English teachers, spending a third of the year with each. At first, I dreaded Al McLean’s class. I had done better with Mr. Blair, an essayist with one foot in the visual arts world who had us writing responses to photographs and answering questions about short stories. After I had rotated to Al’s class, he commented—“Carl, you had a 96 average coming in then dropped to a C. What happened?” I didn’t dare to answer but the correct response would have been, “I have to read longer books and I’m too lazy for that.”

I managed to keep my C, so I passed. It wasn’t all that bad. During one of Al’s segments, we switched from American Lit to The Odyssey. I still didn’t read the entirety of Homer’s work, but I read excerpts. I was a nerdy kid who liked fantasy stories and was an “80’s gamer” with some knowledge of Greek mythology. Al seemed to relax his original sternness a bit once the routine had been established. He mixed some creative assignments with the regimen of essay-oriented tests. Though he continued to rail against our sloth when it came to reading the longer texts, he gave praise when he thought it due. I had written a poem about Greek warriors dreaming after death. It’s long been lost, but it had a line about Agamemnon looking up from his silent city. Al read the entire poem aloud to the class and commented, “Did you write this yourself?”

The question was meant as a compliment. It was unforgettable because I knew he meant it. In a world where endless fake positivity masks underlying ugliness, a compliment from someone who is honest carries weight. I got a C again because I was still lazy. But it was the last year of that.

My first two years of high school were a bit of a torment. I was small and suffered from lung disease. I’d had two lung collapses in my tween and early teen years which had caused air to escape from my lungs and swell my face to the point where the flesh on my cheeks touched my forehead and I couldn’t see. My parents, already bitterly divorced, reacted in different ways. My mother coddled me, though she was single and penniless and could barely keep a roof over our heads. My father (the fun outdoorsman who, as mentioned above, considered himself to have been raised by the military) did not know what to do about it. His worldview, I came to learn later, is of the starkest order. For Don, nature, undisturbed by humans, is the purest existence. Humans interacting well with nature is a distant second. God, literature, and fairy tales are useless bullshit—do you have any more effin’ questions? He was determined to remain strict with me because pity would only throw gasoline on the raging fire of my health catastrophe.

When I got out of the hospital and returned to school, my face had purple bruises. Al McLean commented that it looked like I’d gone a few rounds with George Foreman. Somehow it came across as well-humored and not overdone consolation. But at a time when a young man is supposed to be growing into strength and confidence, I walked the high school’s halls full of confusion and envy. The athletes held hands with their gorgeous girlfriends. The smart kids carried their thick books from the classes wherein they were a year or more ahead of everyone else. I was behind on my schoolwork, short, and sickly.

Orono High School was different from the schools in the surrounding towns (Bangor, Brewer, Old Town). The largest of the University of Maine’s campuses is located in Orono, so many of the kids’ parents were professors. Doctors, lawyers, and other higher income professionals also chose Orono as the place to raise their families. I don’t have a citation to back it up, but I’m pretty sure the acceptance rate of Orono High graduates in the famous and renowned universities of our nation was quite high.

The school itself was physically small, the construction newish, and the doors to the lobby and main office flung open on warm days to let in the sunlight. Visitors were greeted by paintings the art teacher chose from among the student work. You could walk up to the window of the office like it was the front desk of a high-end hotel and do your business with staff that appeared, at least on the surface, to be happy in their work. This stands in contrast to the minimum-security prison of a school my own kids attend in Albany, New York. It is not Albany’s fault, and our family chooses to live in this city and supports the public school. There are many successful students and it has made great strides. But the situation of our effed-up contemporary culture of violence and the general poverty of our population combines to result in a fortress of a facility that struggles to keep academics in focus.

Even Orono High, for a small country school, had a few of these budding issues. Since my father was a Voc Ed teacher, the students he taught weren’t those who were applying to Harvard and Yale. They were mostly heading to trade schools and the military. But even in this, Orono was different. My father wanted these students to know they could succeed and they liked him and related to him. He tried to liaison with the English teachers to bring the importance of writing into focus as it related to his students applying for jobs and doing business. Though he focused on the trades, he liked Orono’s academic vibe because of the respect it brought. He wanted me to embrace it. It was his way of coping with my health issues and a way of trying to push me into the world of doctors and lawyers and a path to success.

I could tell from Al McLean’s classroom discussions that he too liked Orono’s intellectual culture. He spoke of his time teaching in rural northern Maine before he came to Orono with some lament. I even took it at the time as a little condescending, but I think now it was similar to my own father’s thirst for open mindedness and a community that could handle intelligent dialogue over the rote platitudes. The 1980’s were the Reagan years. The controversies of those times seem quaint compared to today, but the seeds of the insanity to come could be glimpsed. Dylan Klebold and his crew were right around the corner. The economy was tough. I don’t think these men loved Orono High out of condescension of the more rural schools but as a desire for an oasis against the roughnesses they grew up with and knew existed and would eventually become unavoidable.

Al McLean wore a jacket and tie every day. Maybe it was the military background. He was passionate about basketball and there were times when I saw his emphasis on Hemingway’s boxing prowess and love for athletes as yawningly spartan.

But there were contrasts.

He wore a Led Zeppelin pin on his lapel. He had poems and New Yorker cartoons tacked to the walls of his office (a tiny room off the hallway near my locker that he called his “cave”). And though he was a sports enthusiast, he also joked about how we should blow up the football field and build a wonderful library. I laughed but was also confused—which is it, I wondered. But Al seemed unbothered by the contradictions. During class, in between working our way through novels, he would bring in random poems and introduce us to more contemporary voices. We learned about Charles Bukowski and Allen Ginsburg. He talked about jazz and the beatniks. He joked about beer and Jim Morrison and there were tales told by students who had seen him hanging out at the local bar in downtown Orono and engaging in various shenanigans. Al was quick to quell any rumors of excess. He made it clear that he did not advocate alcohol gluttony. He spoke with relish about the Dionysian, but he made sure to couple it, in front of his students, with a sense of moderation.

Jacket, tie, and a Led Zeppelin pin.

Things began to change for me my Junior and Senior years.

I grew a little. Not much, but kind of enough. I wore my hair long and swapped the jean jacket’s Motley Crue patches for peace symbols. Of course, teenagers experiment with sub-cultures. I was trying to figure out a way forward, suspicious of sports, suspicious of academics (was I really lazy, or was it something else?), suspicious of my own parents’ motives, but also everybody else’s. I mentioned Dylan Klebold above. The school-shooting situation hadn’t started yet, not really. And I want to be clear that I am not comparing myself to kids like those in the Trench Coat Mafia, but rather, that I had suffered just enough cultural torment to see how bad the problem could potentially become if nothing was done about it.

My lungs were shitty, but I wasn’t weak. In that right of passage that every high school dude had to go through called “the boys locker room,” I held my own. It wasn’t just pushing back physically, though. I liked watching football on Sundays and started talking with the Orono High football players about the sport. We got along. On the occasion some tool effed with me, they at least stopped backing the kid up, so I could handle it on my own. I was just evil enough to let it be known that messing with me was going to result in something far worse for them than simple fisticuffs. And so the bullshit stopped.

But the most important change for me came about through the one card in my hand that trumped all others. I had the most amazing set of close friends who stuck by me. There were two groups—one at Orono High School, the other at Bangor High School (the neighboring town—and yes, the one where Stephen King lives). Some of these friends formed a rock band. These guys were Fran, Rich, and Aaron. Fran would go on to become a professional recording engineer in New York City and work with big name musicians. The other guys were both extremely intelligent and on the road to college and good careers. They were all better musicians than me, or at least, better at their instruments at the time.

The same laziness that caused me to earn a C in Alex McLean’s class had set me behind when it came to music. I was the bass player in the band (anyone familiar with rock band culture, please insert your bass-player joke here). I had been friends with Fran, Rich, and Aaron since elementary school, and so I had an “in” even though my skills weren’t up to snuff. And, like Al McLean, they didn’t pull punches when pointing out, during my freshman and sophomore years, that my chops kinda sucked. I noticed that they were getting good and they were even jamming with older guys who had cool punk bands. Sometimes I was invited to these jams, but I couldn’t do much.

But the band friends stuck with me, and when I finally came around and decided to start practicing, the response was immediate. We would watch the Led Zeppelin movie, The Song Remains the Same over and over and over. I began learning John Paul Jones’s basslines note for note. Rich commented that I was getting faster. Fran noticed that my chops were improved and, as the “pro” musician of the band, patiently showed me new licks on the bass and on the guitar.

Even my grades in English class were improving. I was earning A’s in Mrs. Gilles’s British Literature class. For some reason I had more patience with Shakespeare than I had with Faulkner. Mr. Ingraham taught George Bernard Shaw’s Saint Joan, and I ate that up, too. I skipped Al McLean’s upper-level American Literature class in favor of Mrs. Gilles’s AP English wherein we read Moby Dick. This class was a challenge and my essay grades varied. But I devoured Melville’s novel, then read it again. For some reason, I could read.

I sometimes stopped by Alex McLean’s “cave” to talk about books and hand him some poems. He was always glad to have a visitor and read all of the poems. I was steeped in band culture and seventies lyrics at the time and I think it was having a detrimental effect on my teenage poems, but he read them nonetheless and commented objectively. I regretted that I never took one of Al’s classes after I had gotten my “sea legs” when it came to engaging literature. But it didn’t matter, the conversations were good.

The rock band was playing high school dances and the microcosmic fame had more or less made high school endurable. This didn’t subtract, however, from the immense feeling of emancipation I felt at graduation. I have read biographical stories of heroin addicts talking about the first time they shot up and how it was indescribably orgasmic.

That’s how I felt when I was free.

Al McLean said to me after graduation, “You won’t be back here. The kids who come back around are needy. You won’t be back.”

He was right, though I wasn’t exactly at some kind of glorious cruising altitude. I still didn’t know what to do. I couldn’t join the military like my father because of the lung. My grades weren’t good enough for a high-end college. I had no money and was not underwritten by family. So like a lot of OHS kids, I applied to University of Maine at Orono and got in. We jokingly called it “grade 13.” Except this wasn’t accurate. It was the beginning of something different. I had left my high school cover band behind. Without subtracting from the appreciation I hold for the friends who stuck by me, I was glad to be writing original songs and playing with musicians who were more willing to experiment. I kind of fell in with the “hippy” band subculture, and had this surreal folk duo with my friend Sean that played gigs around Bangor and then southern Maine.

During the time I was going to college in Orono, there were rumors that you could go talk about books and maybe drink a beer with an old English teacher, Alex McLean, at his house on Margin Street. Because I had gone to the local high school, I remembered Al talking about his home “on the Margin.” He touted this street name as a useful metaphor for what it is like to live on the border of the formal and the informal, the organized and the disorganized, the Apollonian and the Dionysian.

I used to walk down the railroad track that crossed through Orono on the way home from the college campus. I would play my harmonica as I went and sometimes I ran into Al on Margin Street, which bordered the tracks and the river basin. He would say with a smile that seeing me walking on the tracks with the harmonica was the portrait of contentment. He would often make reference to Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s line about “Buddha in the woodpile” and how this was a Zen moment.

There were a few other times I stopped by the Margin. I moved in the same friend circles as one of Al’s daughters, and though we weren’t close, was acquainted enough to say hello to them when they were living at his house. I considered stopping by more often for a beer but was haunted by his words from the high school days about moderation. When I thought of Al, I thought as much about his formal side as his Dionysian side. There were undergrads and graduate students at University of Maine who formed closer friendships with Al, some of whom I didn’t meet until years later. There were stories of hedonism on the Margin. These were interesting and yet I didn’t try to get involved (if there was even anything to get involved in), and then I moved to Portland, and then South Korea, and then New York, with other travels in between.

Years later, when the internet came along, I reached out to Al on social media. We corresponded a little. I am shy about high school reunions and a bit cynical with regard to nostalgia. I have many good friends from high school days with whom I’m still close. I am not misanthropic, not totally, but the memories of the tormented side of those times are enough to make me cautious. I liked keeping in touch with Al, though. Our correspondence was infrequent and maintained an affectionate distance. I had graduated from University of Southern Maine with an English degree. I had an interest in postmodern literary criticism which I don’t think Al shared (we didn’t talk about it). We did sometimes argue about Hemingway and Kurt Vonnegut. He made it clear to me—“I vomit on anyone who disrespects Vonnegut.”

I think he misunderstood my take on both writers, particularly Hemingway. I love Hemingway, but I don’t see him as a Realist. I see him as a Romantic. His descriptions attempt to imitate reality, but in the end, I consider him idealistic. Our world is one of dirt and parasites, not boxers with poems on their lips. To become the latter is to deny reality.

Al and I disagreed but within a few lines we were talking about cracking a cold one. He teased me about my over-fondness for Yeats but he also liked Yeats and recognized the musicality of his lines.

These days I work a corporate job in New York City. I have a house in Albany, New York, and perform with some amazing local musicians. In the years before, I abandoned songwriting in favor of poetry and then novels. I’ve written and published three novels with a small press. One of them got some attention online some years ago. I write “genre fiction”—horror, and some fantasy. Though the characters in the stories do things that are “impossible,” I have a habit of layering a lot of realism into the descriptions. A writer shouldn’t analyze their own work, in my opinion, but suffice it to say it’s possible the stories occupy a borderland between the real and the unreal. It may make the stories weirder and not in line with works more formulaic.

My correspondence with Al McLean continued up until his passing last week. It turns out that not only did he teach at the same school as my father, but they entered the same VA facility in Bangor, Maine, as their health conditions required (though the conditions themselves were different). Al took some nice pictures of Don while he was there and sent them to me. He relayed some kind words Don said about me, retrieved while they were hanging out and undoubtedly by sifting through my father’s dementia.

I sometimes wish I had been able to visit Al when he was still living on the Margin. In recent years, when I went home to see my parents, I would walk down to the tracks and have a beer at the brewery by the river basin. I would walk up to Al’s door, on which there was a sign, “Literary Counseling,” and give it a knock, but I was too late. Each time I came, he was not home, and by the later attempted visits, I suspected it was health related. This was the price of the “affectionate distance,” but ultimately, I don’t regret the way things went. There is value in understanding how to live on the borders, and this is a price worth paying. It isn’t about the good and bad, the just and unjust, the black and white, or even the gray. It’s about carving beauty from the edges. Thanks for turning me on to this, Al. I’ll see you somewhere on eternity’s margin.

Photo of Margin Street by Airdrie McLean

Carl R. Moore is the author of Slash of Crimson and Other Tales, Mommy and the Satanists, Chains in the Sky, and Red December, published by Seventh Star Press. He has published numerous short stories in magazines and anthologies, most recently with Jumpmaster Press and Crystal Lake Entertainment.

If you ain’t standing on the edge, you’re taking up to much space, Scotty Townsends t shirt, you can YouTube Scotty townsends memorial video if you wanna

Thanks, I’ll check it out!

I can imagine reading this in The New Yorker.